Now I knew what was needed, what didn't work, and what had to be redesigned for the 1997 attempt.

After my return home, the first order of the day was to go back to my shop and make some money. About this time Sid and Matt Biberman, with Bill Jean, Sid's partner, came to the house to see the beast. They lived about 100 miles away in Norfolk, Virginia, and although I had talked several times to Big Sid, I'd never met him personally. The liner had been setting in my garage where it had been parked for over two months. I didn't even know if it would start, but decided to start it anyway. In no time atall, "lo and behold" the thing roared into life.

Sid, Matt, and Bill seemed to be thoroughly impressed with the monster I had created. After seeing and hearing Black Lightning run, Sid decided to put it into his book, VINCENTS WITH BIG SID, in the article, "The Lair of the Mountain King". I appreciated the kudos in his article, but my goal was then, and still is, to see the Vincent logo reign supreme, once again becoming the dominate motorcycle in the world of speed, the one to be at, "The World's Fastest".

With this in mind, the project began for the 1997 attempt. First I had to figure out a way to raise money to support the hungry beast. I decided to ask for contributions for the first time from the British motorcycle community, particularly the Vincent Owners Club.

Without going into detail (which is a story in itself), let me just say that the President and others of the VOC helped. I might add without their help the project could not have continued. The President of the club Brian Phillips, rewrote my begging letter to the club, John Webber, the then Editor of the club's magazine, MPH, personally donated half the postage on their end for the mailing, the other half being donated from the VOC club coffers, and I provided the written and photographic printed material. My wife, Patti, organized the five sheets contained in each packet, stuffed it all into 2500 manila envelopes ready for John Webber to mail. I packed the boxes and sent them to the Editor in England, as the club's membership names and addresses are private.

On this side of the pond a similar mailing was sent out. John Healy, of Coventry Spares, helped on this end, providing me with run off mailing labels for the Triumph International Owners Club, and by writing an article in their quarterly club magazine.

The response was overwhelming.

(Nor were these the only clubs. All in all fourteen motorcycle clubs have contributed to the project to date (June 2007.) They are: BC CVMC, BMOC, BRIDGEND DISTRICT MC, BSAOC, Culcheth MC, Laughing Indian Club, ARMA, BIMA, Black Shadow MC, TIOC, VOC, Vintage MC Enthusiasts, Vintage MC Club, and Northern Alberta section of the Canadian Vintage M/C Group. Twenty-nine VOC Sections, forty-four businesses, and over 600 individuals have contributed to the project since my request first went out in 1997.)

The 1997 pilot was Stu Rogers. I first met Stu at Daytona during Bike Week in 1995, where he was running his Norton Manx in the pre-1940 Vintage Class. We hit it off immediately, as I had run a 1938 Manx a few years earlier in the same class at Daytona, finishing a photo finish second. My rider had been the man in black, famous Italian racer, Marcello DeGucci.

While I was going on about Marcello etc., Stu was climbing into the Vincent liner to try it on for size. Observing that he made a good fit, I offhandedly asked him, "How would you like a ride sometime in this rocket?" To my surprise he replied, "Tell me when and where and I'll be there." I knew he wasn't joking. Stu, as most of you know, is a world class road racer, and he is small. I figured Don Vesco, with his Turbinator, already had his plate full. So I contacted Stu again early in 1997, and asked if he was still interested. He answered without hesitation, "Yes", he wanted the ride. All of this happened before I sent out the cry for help, the mailing request for contributions.

Around 9,000 pounds went into the English account managed by Stu Rogers, and about $10,000 into my U.S. Black Lightning account, bringing the total to around $25,000 U.S.D. in 1997. Other contributors were Ron Kemp, either donating money, parts, or parts at cost. I believe Trevor Southwell provided a machined aluminum transmission door from Billet that year. So many people were willing to help the project in any way they could. A feeling came over me then and is with me still--I must not fail.

The money was now available, and I still had five months before Speed Week to build a new streamliner--liner number four. I set to work building the new frame from 4130 chrome moly tubing, using approximately 30% of the existing frame. A pedestal containing a plenum chamber was made for the blower. It was robust in design to keep the blower from twisting and throwing the blower belt off.

The roll cage was raised 2 1/2 inches so the rider could sit up higher in the bike in order to see over the nose. The change increased the frontal area to 3.7 sq.ft. I overhauled the engines--ring job, valve job and so on. The drive line was modified, changing the triple row chain and sprockets to a 1" wide HYVO chain. A clutch was manufactured by ART, they make clutches for drag bikes that produce 500 hp. Cost $3500 with spares. I wasn't about to go back to the salt with a clutch that wouldn't do the job.

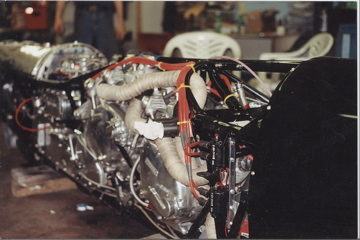

There were a few major engine problems I had forgotten about, one being that the front engine had twisted at the spline about 10 degrees on the drive side main shaft on the crank. Not enough thought had gone into why. I remember thinking that must have happened when the cammed portion of the front primary chain dampener shattered. I replaced the shafts. Another problem was that the engine cases through bolts were coming loose. New engine plates were made and welded to the cases. Now it was impossible for any shock loads between the cases to cause the bolts to loosen. The Rita/Lucas system was removed. That yellow spark which would only allow the engines to turn 4500 rpm was not going to the salt this year.

After a little research on the matter of ignition systems, I selected a German run company called Nology to build an electronic ignition system specifically for the bike. The Rita/Lucas system was sent for analysis. The new ignition system soon arrived on my doorstep C.O.D., and I wrote a check for around eleven hundred US dollars. The spark plug wires costing $400 of the $1100. Inside the package I found a hand written note saying, "I don't know how you ever got the bike to start. The ignition system you sent us would probably work O.K. on a street bike, but would never work on a blown fuel bike." They didn't have to say that. I already knew it didn't work.

I installed the new ignition system, turned over the engines, and the prettiest spark you ever saw appeared--white with a cast of blue, and you could hear a cracking sound when each plug fired.

Months had passed, and it was now into countdown time. I only had 45 days left to complete the liner, so I called Stu Rogers for help. I stopped work on my restoration business, and was now working full time on the liner, 10 to 12 hour days again.

When Stu arrived I immediately put him to work. About two weeks later two of his friends arrived, and I put them to work. Even with this work force, the liner progressed slowly, and it was time to head for the salt. I was beginning to think that streamliner building isn't so easy.

We were running behind schedule. We had built a single rail salt trailer to better retrieve the liner after a run, and it wasn't finished. This year I built a whole new body, and the wind screen canopy wasn't yet installed. The new tow bar for towing the liner wasn't finished. I'm sure there were many other things that were wrong, which I can't recall. This is not my favorite memory, so I probably have a mental block of some sort going on. One thing I do remember. I had borrowed David Baxter's mobile home to help defray the cost of motel rooms. The mobile home was old and needed a lot of work. We spent hours and hours repairing the motor home--brakes, generator and so on. These hours of work would have been better spent on the liner.

One day of Speed Week was already gone and we were still sitting in Virginia. It was about one in the morning, and as I recall, we had only fired the bike a few times. Not much testing at all on the engines. I had a few oil leaks, and the air speed indicator had shaken itself apart. I had just finished painting the new body that day, and it was still wet when we loaded her for the 3000 mile trek to Utah. Stu and company were in the motor home. Mike Shea and I were in my truck, with the liner behind us, drying on the trailer.

We drove straight through. We took 42 hours getting there, as we stopped only for gas, to tie down the streamliner, which was about to exit the trailer, and to place the 55 gallon drum of alcohol upright. It had rubbed a hole in the drum due to improper securing.

We were keeping an eye on the weather, which was beginning to look ominous. What else could possibly go wrong? I was really feeling the pressure, as the $25,000 was almost gone. Ron Vane from England, and Roberto Crepaldi from Italy were supposed to fly over.

I've always felt that when confronted with a situation as desperate as this, you just do the best you can, and everything will work out in the long run--only I was doing my best and so far nothing was working out.

We arrived on the salt and set up the pit. This was already about noon on the third day of Speed Week. I found out later that Roberto Crepaldi had arrived and left, thinking last minute problems with the liner caused a no show. He wouldn't have been far off. Stu and company arrived about five hours behind us. Sonny and Don Angel, Dave Breeden, and even Don Vesco were already there. The rest of the third day was taken up with tech, putting the wind screen in, and fixing the tow bar and salt trailer. That was when I met the four Vincent enthusiasts who had come down from Canada.

The weather was horrible, wet salt and all. The morning of the fourth day was taken up with the finalization of tech. I got a sticker on the nose of the liner. I had a couple of things to do, fire the engines and pit tune them a bit for altitude, and give Stu Rogers a dead engine tow up. Keep in mind Stu had never ridden a streamliner before. Few have.

I fired the engines. The liner was starting hard, lots of backfire through the blower. I figured that I'd created a design flaw in the new plenum, and in the duct work to the cylinder heads. It didn't do that with the previous manifold in 1996, but with a little fiddling I was able to figure out how to start it without backfire. After a clean start and the engines were warmed up, I wicked it a couple of times. It sounded good and strong. Then it started shaking. I'd lost number one cylinder. Now what? A quick inspection revealed that the exhaust valve push rod was bent on number one cylinder. The cam cover was removed and I also found that the cam valve lifter had broken. The lifter had been improperly heat treated. The next thing that happened in testing the multitude of systems required on a streamliner, was that the clutch was engaged. Stu, who had installed the clutch, had left the Kawasaki style thrust bearing out.

We were all really tired by the time this was done, and human error multiplies 10 fold when you are tired. When the clutch peddle was pushed, it forced the slave cylinder out of it's bore, destroying the seal. This was a real problem, as I had brought no spares.

About this time one of the Canadians volunteered. I figured we needed all the help we could get, so after hearing their credentials, this was going to be the plan. I put two of them to work fixing the push rod and broken cam lifter. I had brought spares for this. I had to drive into Salt Lake City over a hundred miles to the east of Wendover to get a seal. It was a Honda V65 slave I used. A call to the Honda shop was made to ask them to keep their doors open. I asked Stu and the others to get the tow vehicle ready for the next day's tow up.

Off to Salt Lake City I went, got the part, and returned four hours later The repair to the engine had been made. The tow vehicle was readied. I quickly installed the new seal, bled the lines. The bike was ready to go! By this time it was too late to do the tow up. So off to the motel we went for a well deserved rest.

The next day the crew was there at dawn. I started the engines and she sounded good, firing on all four. Dan Smith and John MacDougall had done a good job. We found a place to tow it up. About three tow ups were made, and Stu said he was ready to make a run. It was now day five, about noon. We took Black Lightning to the line with high hopes.

I'd told Stu earlier that morning that I'd talked to Don Vesco, who was the back up rider. I said to Don that we were in a real bind as far as time. There was no time to get Stu his driver's license, as a new rider has to work up to each level of speed. He is allowed to go 125 mph, 150 mph, 175 mph, and so on. Stu realized what I was saying. Don Vesco was going to be the rider. I also told Stu, "After all the work and effort you put into the project, you deserve at least one ride." I then laughed and said, "Don't crash it!"

We went to the line. Stu was pulled up to tow speed. He released. The run looked good. He accelerated slowly to about the one mile mark. I was in my truck following the liner down. This is where I'm not clear to this day as to what happened. The liner could not have been going over 130 mph. It abruptly fell on it's side, then rolled once, tearing the canopy off, then on one side, then the other, eventually sliding to a halt. The parachutes deployed, as they had been designed to do in the event of a crash.

My first thought was of Stu's safety. I drove as fast as I could to the crash sight and I saw Stu climbing out of the now not so pretty liner. He appeared all right. What a relief that was. Now my thoughts went to the liner. Could we fix it?

We got the liner back to the pits. The officials were there. They said after a crash the tires would have to be replaced, and the liner would have to go back through tech after all repairs were made. This was impossible. No tires. No wind screen, which had been shattered in the crash. A lot of body work would be in order.

That was the end of the 1997 effort. A ton of money and untold man hours were all dashed in a split second.

I've heard three stories told about the events which let up to the crash. I don't know which one is true. Henry Louy, the track official who was observing the liner's run, thought it sounded like one engine quit running, and then it took off at the one mile mark, just as Stu raised the skids. The salt was real wet at the one mile mark, and several cars had spun out during the week at that point. Another story was from a spectator who was at the one mile mark not more than a hundred yards away filming the run. He said that the liner was not on it's wheels, and when Stu raised the skids it just simply fell over. The third story came from Stu. He told me he had it up on it's wheels, and when he really started to get into it and raise the skids, the rear wheel broke traction and the liner fell over. I don't think we'll ever know what really happened.

The week ended with a performance, now part of history, of which I'm not proud. I thought about how I'd let the good people who had given me financial support down, and how my efforts had fallen far short of my expectations, and I supposed the expectation of others. With these thoughts in mind, I made a pledge to myself. One, that I was going to return to the salt with a new liner in 1998, correcting all of the mistakes, both mechanical and human, and two, it was going to be done with my money. So I formed a plan to do this. I made the trek from the salt to Joplin, Missouri, and looked at a house that Dave Breeden had told me about, vacant, and for sale. It had a huge 50X50 shop with three phase electricity. After I called my wife, I made a lease purchase agreement, and left the liner with all the salt stuff, tent and so on, at Dave's house in Missouri. I then drove back to Virginia with the streamliner trailer, loaded all of the Vincent basket cases, about 10 in number, and all my tools, which included an old worn out Clausing lathe and a Bridgeport mill. I had already partially restored two of the basket cases, one Black Prince, and one Black Shadow. Both were already sold. With a rented U Haul truck, a boat load of Vincent stuff, and all our household furniture, Patti and I made the move to Joplin, Missouri.

The shop was beyond my dreams--fabulous. It had the works: sleeping quarters, kitchen, shower, workbenches and most importantly, plenty of room. The first thing I had to do to raise some money for the next Bonneville attempt, was finish the Black Prince.

|